I Political Symphonies

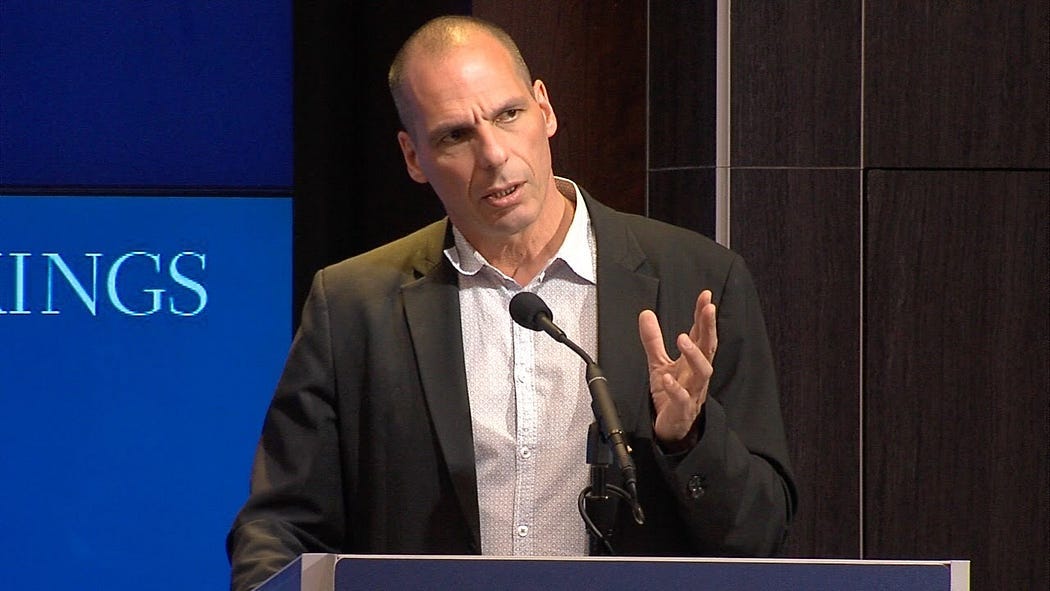

As Vintage’s resident ‘erratic Marxist,’ Yanis Varoufakis recently had the opportunity to pen an introduction to the new reprint of The Communist Manifesto. There he expounds on the nature of great manifestos. To succeed, he says, a manifesto ‘must speak to our hearts like a poem while infecting the mind with images and ideas that are dazzlingly new.’ It must open our eyes to possibilities for progress, while it reveals how we have acted as the accomplices of stagnation. And most importantly, it must resound with ‘power of a Beethoven symphony,’ inspiring ‘humanity to realise its potential for authentic freedom.’

To me, this final part of Varoufakis’ description is slightly askew. While Marx and Engel’s great manifesto may crash upon its readers with the weight of a great orchestra, the document is really more like a solo performance. Manifestos are univocal in the extreme – like ‘a violin in a void,’ to quote Nabokov.1 They sing with one voice, and their climb towards some blinding, euphoric peak is a lonely expedition. In contrast, the symphony relies upon counterpoint, dissonance, harmony. It lives on the effects that exceed the sum of its many parts. Symphonies are truly polyphonic works, clouds of rich texture produced by an army of performers. Rather than a monologue, symphonies hold in their hearts the messy clamour of a conversation.

In Another Now, a book that could have been his most manifesto-ish work to date, Varoufakis completely ignores his own advice – but in doing so, he gives us something properly symphonic: a ‘political science fiction novel’ about an alternative economic reality, filled with Socratic dialogue, the truth of which emerges through the collision of its cacophonous voices. Instead of another tired manifesto Varoufakis has produced something rich, indeterminate and symphonic, a work that hums, agora-like, with political and philosophical polyphony.

II A Realistic Utopia

Another Now revolves around a hopeful snapshot of a parallel universe where an alternative to our present capitalist system was established in the years after the GFC. Varoufakis’ vision could have taken an unbounded number of forms; but, cognisant as he is of the tyrannies of capital, the state and hierarchies of power, he gives us a world where capitalism has been replaced with a radical yet pragmatic system of technologically-driven anarcho-syndicalism.

The reader is introduced to this progressive dreamland through lead character Costa. A brilliant but politically disillusioned engineer, Costa labours for years to create HALPEVAM,2 a machine designed completely satisfy our individual preferences. With this machine, he hopes to confront the world with the logical conclusion of consumer society. But as he works on this invention, he accidentally creates a portal to ‘Another Now.’ Through this tiny wormhole he starts to send and receive dispatches to Kostis, his equivalent in the other world. By doing so he learns of a world where capitalism died after the GFC, and the world transitioned to democratically run, worker-owned corporations, where each person holds an equal, non-transferable share in their company no matter their role.

Massive changes followed this transformation. Share markets, investment banks and private credit creation were all eliminated. Land ownership was socialised. There was a thoroughgoing democratisation of the whole economy and a Universal Basic Dividend is paid to all citizens of the world. Together, these changes cleansed markets of their fatal flaw—capitalism—finally allowing for the triumph of experiential value over exchange value.

What we find in Another Now, then, is a hopeful vision. It’s a humanist’s practical paradise, a world that Costa—speaking, we presume, for Varoufakis—says is ‘closest to [his] heart.’3 Most attractive is the feasibility of this system, a quality that gives us the sense that there is a real chance for political progress. Instead of our dystopic, ‘intolerable’4 Now, where we ‘act as if our lives are carefree, claiming to like what we do and do what we like’ but where ‘we cry ourselves to sleep’ or endure ‘anxiety-induced insomnia,’5 the book shows that our present situation is contingent, and how a realistic utopia could emerge.

III The Agora on Paper

As an economist-philosopher, Varoufakis could have written Another Now as another didactic tract, crammed with technical information, historical excursions and theoretical flourishes. Instead, he tries something more radical, giving his dream of Another Now to a diverse team of interlocutors—Costa, Iris, Eva and Thomas— who debate, critique and ultimately accept or reject the chance to live in the alternate world.

Costa, as the purveyor of the dispatches from the Other Now, unambiguously favours its political reforms. But the other characters are more critical. Iris, the book’s Marxist-feminist and ‘thinking radical’s thinking radical,’6 is a militant sceptic of the Other Now; though it has undergone radical economic reform, the alternative reality still defends patriarchy with a socially conservative language of political correctness.7

Eva, the book’s libertarian, market-fundamentalist voice, supplies a counterpoint to Iris’ radicalism. She speaks with the voice of the economic establishment, and her dogmatism brings conversations to an impasse. Yet this is not counterproductive. Instead, her resistance shows us how political discussions are hopelessly normative and irrational. Our axiomatic beliefs cannot be secured by appeal to reason, logic or other transcendental signifiers; politics is ultimately a matter of feeling and faith. Though Eva embodies this emotional rigidity, she eventually warms to the Other Now; her narrative finally shows that open, vigorous discussion can clarify our fundamental beliefs, giving us a lucidity that can ultimately lead us to change our positions.

Eva’s son Thomas arrives as a final supplement to the discussion. A conspicuously sad, impotent teenage boy who ‘yearns for power,’ Thomas admires and submits to ‘absolutist, patriarchal power’8 wherever possible and acts as a vessel for the ‘wider political malaise’ that afflicted young men across the world throughout the 2010s. Where other leftist activists would be content to shame or denigrate these lost boys, Varoufakis displays an admirable sensitivity: refusing to abandon him to figures like Jeff Bezos and Jordan Peterson, he outlines for Thomas a way to engage with progressive politics that appeals to his all too human need to feel powerful.

Reading Another Now, there is a sense that the conversation, much like that of a true democracy, is never finished. Though the book offers a concrete and well-wrought alternative to capitalism, readers will find themselves beset by lingering, internal disagreements, arguments pregnant with contradiction that have crept from the page into their life. By assembling this disparate group, strategically plucked from points across the political spectrum, Varoufakis creates an approximation of an ancient Greek institution: the agora, that bustling assembly where the polis once gathered. Another Now is a drawing of the agora that transplants the public arena’s restlessness and lack of closure into the reader; above all, it is a noisy, messy democracy in action.

IV Radical Indeterminacy

Another Now is more than an argument for techno-syndicalism. More fundamentally, it depicts a democracy in action, untidy and unclosed. At the level of its content we find a democratic pattern, a swirl of indeterminacy. And remarkably, Varoufakis manages to carry this motif over to the form of his novel as well, giving us a final involution that harmonises the book with his broader intellectual project.

For many years, Varoufakis studied economic theory to show that it fails on its own terms – that its pretensions of objectivity, rationalism and deterministic closure are dangerous fallacies. Drawing on Marx and Keynes, he often argues that creative human work and our beliefs about society cannot be reduced to any kind of formula: ‘decisions affecting the future… cannot depend on strict mathematical expectation,’ Keynes wrote, ‘since the basis for making such calculations does not exist.’9 Varoufakis also believes that a scientific notion of value is impossible because of the latter’s dialectical nature: ‘social power is determined by our valuation of things, of people and of their ideas and, at once, determines these values.’10 We are open-ended and protean; humans are undefined and forever react in unpredictable ways to new phenomena. Our human condition ensures we will always resist the economist’s attempt to capture our behaviour in mathematical models.

Varoufakis believes that human behaviour is radically indeterminate, and his book reflects this notion. Instead of providing neat closure, Another Now is filled with impasses, disagreements, obdurate resistances and changes of heart to which the reader adds their own objections and endorsements. Our interpretation of the Other Now—and by extension, our own political beliefs—is unfixed, unpredictable and free. Indeterminate, in a word.

In an article for The Guardian, Varoufakis told us that writing Another Now ‘as a manual would have been unbearable. It would have forced [him] to pretend that [he had] taken sides in arguments that remain unresolved in [his] head – often in [his] heart.’11 Even now, his own views are like those presented in the novel. Both Varoufakis and his book are polyphonic, shifting, disputatious. But rather than evasiveness or indecision, this statement is a portrayal of his most fundamental conviction: that ‘learning to embrace indeterminacy is part and parcel of attaining a higher order of rationality.’12 From his politics, we can see that Varoufakis tries to live by his own words; it is also clear that Another Now is a continuation of his indeterminate performance.

Both man and book are images of the ambiguous openness necessary to the progressive conscience. Together, they form a picture of the permanent revolution of the heart and mind essential to human progress. They are equally democratic in form – brilliantly, necessarily polyphonic. We ought to listen to his message with all the attention we might give a great symphony.

Endnotes

Who, with his disdain for Marx, probably would have hated being quoted here. In The Gift, Nabokov can only stomach the inclusion of a Marx quote by arranging it in blank verse to make it ‘less boring.’

I.e., the Heuristic ALgorithmic Pleasure & Experiential VAlue Maximiser, first encountered in Varoufakis’ Talking to My Daughter where it was created by a character named Kostas. As it is described in Another Now, HALPEVAM is rather like ‘The Entertainment’ in David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest. Both are pieces of technology that provide their users with ‘a truly dizzying form of rapture’ and both threaten our society at a fundamental level. Yet in my view, Varoufakis’ HALPEVAM is more sophisticated than Wallace’s Entertainment. Unlike Wallace’s Entertainment, a film that captivates its audience by offering the same, entrancing and apologetic mother figure to all who watch it, HALPEVAM relies on the idiosyncrasies of each individual’s fantasy. In this way, Varoufakis is more progressive than Wallace: he does not assume that there is some essential form for our desires that can be captured by a single image, or that we share some common misogynistic dissatisfaction with our mothers. Varoufakis also sees the political implications of his character’s invention more clearly. Terrorists try to use The Entertainment to attack the USA in Infinite Jest, but Another Now assumes that the corporations who wish to monetise the technology are the greatest threat to society. Were it real, corporations would use HALPEVAM like they have used addictive smartphone apps, creating a cycle of dependency in consumers using their product. For this reason, I think the social theory underlying Another Now is both more realistic and more unsettling than the one in Infinite Jest.

Another Now, p.85.

Varoufakis’ words in the dedication section of Another Now.

From Varoufakis’ introduction to The Communist Manifesto.

Another Now, p.8.

Through Iris, Varoufakis also makes his first critique of political correctness and romantic relationships under capitalism. In line with his other views, his is a rather Hegelian feminism. It’s a proper dialectics of desire, and he deploys it to give us the book’s best moment – a speech, delivered in the Other Now, on love, sex and consent.

Another Now, pp.193–7.

The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, pp.162-3.

Modern Political Economics, p.49.

Modern Political Economics, p.69.